Steve Miller at Universal Concepts Unlimited

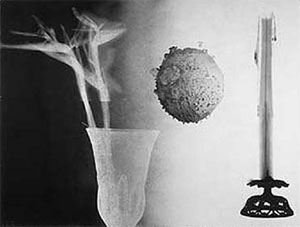

Steve Miller: Self-Portrait Vanitas, 1998. Mixed mediums on paper, 38 x 50 inches; at Universal Concepts Unlimited.

In “Neomort,” his first show in the newly opened Universal Concepts Unlimited (a Chelsea gallery devoted to the intersection of art and technology), Miller investigates psychological states. He is a researcher who happens to know color theory. For more than two decades he has been finding ways to link his fascination with scientific toys and tests with his affection for painting, which, despite his tango with technology, remains his primary mode of expression.

“Neomort” is a sci-fi term for technically dead humans kept alive by artificial breathing devices. The 17 works in this series are based on X rays or other electronic and digital scans of objects Miller associates with 17th century vanitas paintings: skulls, wilting flowers, musical instruments. In assuming the role of grim reaper dressed in a lab coat, Miller takes everyday things, runs them through diagnostic procedures, and marks them “terminal.” He does not spare himself: several of the works (spray enamel and silkscreen on paper) are called self-portraits. In a particularly haunting one (#126, 2000), a thin branch with a few flowers clinging to it seems to float atop a barren charcoal landscape. Memorable for its spareness, this self-portrait suggests not only the finality of death, but also the spirits attempt to linger among the living, if only for a while. In other works it seems as if the artist speaks from the grave, employing a life-size guitar to remind viewers that he once had a full life, of which music was a pleasurable part. Candles, half-empty vases and clocks suggest the passing of time, which, in traditional vanitas paintings, can refer to both the transience of life and the speed with which death can make its claim. Interestingly, Miller’s silkscreens are not, by and large, morbid. His use of pop shades of red, blue and orange hints at a lightness about death, or at least a sense of reconciliation with the fact of it.

Miller’s work is important at this particular moment of techno-exhilaration. He uses the machines of medical technology to warn us of the vanity in thinking that our newfangled gadgets and super-speedy processors might somehow spare us the inevitable. It may be postponed, but it will not be denied.

-Michael Rush