Building Blocks

Exhibition features high-tech pieces inspired by the jottings and writings of a Nobel Prize-winning scientist

By Cate McQuaid, Globe Correspondent – October 14, 2007

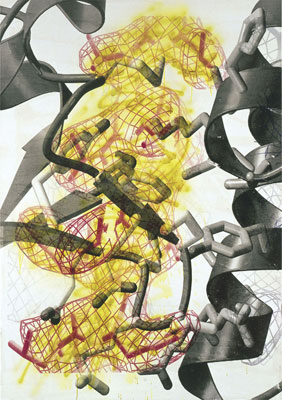

Steve Miller - Liquid Wrap, 2006. pigment dispersion and silk-screen on canvas. 57 x 39.5 inches, 145 x 100 cm. collection Martha McGarry, New York.

More than you can imagine, as revealed in Steve Miller’s dark and startling show at the Rose Art Museum at Brandeis University. The paintings and prints in “Steve Miller: Spiraling Inward” spring from the research of biophysicist Rod MacKinnon, whose studies – of how the movement of charged ions across the membranes of proteins to cells generates nerve impulses – won him a share of the 2003 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Miller, who gave up painting for high-tech installation art in the 1980s, continues a long journey back to his artistic origins in this show, which is all about origins – the beginning of life, and the codes that define who we are. For Miller, those codes begin with the jottings, equations, and diagrams from MacKinnon’s notebooks. They include Miller’s own artistic DNA, which spirals back to Pollock, Rauschenberg, Warhol, and Yves Klein, and a visual language of scientific models and photographs of high-tech devices.

The exhibit starts in the downstairs gallery, with prints that elucidate Miller’s strategy. They’re like duets compared to the more orchestral works to come. Some, such as the silk-screen “Protein #220,” simply apply the artist’s compositional sense to protein models, which look like looping plastic belts and joints. They twist through empty space into a loose, rhythmic abstract work, with two of the circling belts hovering like empty eyes gazing at the viewer.

“Protein #364” features a graphite drawing of one of Picasso’s sculptures inspired by the forms of African art: sensuously round comma-shaped forms, snugly embracing one another. Miller has silk-screened a scientific image of a protein right on top of it, puffy and floating like a cumulus cloud, with passages in black and white. The contours of the two forms roughly match. The protein appears, in some ways, to contain the sculpture, or perhaps the sculpture has emitted the fog of the protein. The artist links an art-history building block with an organic one, and they make an odd but pleasing fit.

The works get painterly when they hit the canvas. In fact, Miller silk-screens onto his canvas; he adds and erases, as if painting, and each piece is unique. He pays such attention to surface and material these works take on some of the classic issues of painting. Figure wrestles for dominance with ground. Abstraction and figuration tense against each other, as a third element – notation – insinuates itself into the ring.

“Soap Opera, the Second Season” has the fewest such layers, but it’s a gorgeous piece. Another model, this time of clustered molecules looking like a voluptuous bunch of blue and white grapes, hangs suspended against a white ground between two burbly liquid passages of blue, like cells spontaneously gestating from the primordial ooze.

Miller has been making this series of works since 2002. The most recent pieces, and the most ambitious, fill the upstairs gallery. They’re black and white, stark and roiling, as in “At Any Given Moment.” MacKinnon’s notes, photographed and silk-screened, form one layer, a murmur of words, equations, and diagrams in the scientist’s own hand – opaque to the non-scientist, but conveying a diary’s intimacy. Great, drippy washes of dark paint bracket the scene. At the bottom, the inky black looks like straight-on paint, but at the top it silvers into a haze rippled with texture. On top of these spiral more belt-and-joint protein models in white. The dizzying interplay of black and white makes it impossible to tell where this all started; what appears to be the bottom layer switches out to the top. Miller slyly adds a little computer code at the bottom that suggests that the whole thing is a TIF (computer image) file, adding yet another language to the mix.

Then there are the photos: In “Potential Difference,” clusters of S-curving computer cables mix with swipes of black paint; they’re so in synch it’s hard to distinguish between the photographic gesture and the painterly one. “If They Exist” has at its core glimmering silk-screened photos of foil-wrapped synchrotron light sources from MacKinnon’s lab; they arise out of a central puddle of black paint, which coalesces from horizontal drips and streaks across the canvas. The white ground often encroaches surprisingly onto the darker image, as if about to swallow it into nothingness.

In Miller’s paintings, Rose director Michael Rush suggests in his catalog essay, “The race to understand life, exemplified in the swift, urgent jottings in MacKinnon’s notebooks, is ultimately enmeshed with an endpoint: death, the black hole, revealed.”

I don’t find them that heavy. Miller certainly dances with death in “Spiraling Inward,” but the dance itself is an affirmation of life, which keeps miraculously generating and regenerating. Despite all the endpoints, in the big picture, it never ends.

© Copyright 2007 Globe Newspaper Company.