Considering the Clarity of X-ray Photography

by Seph Rodney, 09/05/2017

Ultimately, in the collection of images, one can see the painter and contemporary image maker that is Miller vying against the Miller who is more sentimental.

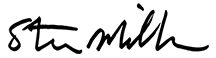

Steve Miller, “Torch Snake” (2011) inkjet on paper, 24 x 36 inches

One of surest ways to generate interest in a technology that has been in use for some time is to combine it with a new idea. For example, take X-ray photographs of objects, both animated and inanimate and introduce them as illustrative of our networked world and the notion that each discrete human being is essentially a space of molecular flows, an interchange where energy moves through matter.

It’s this compelling theme that Steve Miller uses to ground his book Radiographic: X-ray Photo Inventions. X-ray photography has been used to make art, only a few years after 1895, when the German scientist Wilhelm Röntgen discovered that electromagnetic radiation could affect photographic film and provide images of dense materials surrounded by less dense matter. The foreword to the book, written by a science writer and academic, Carl Safina, guides the reader toward that penumbra space where science and art overlap, urging serious consideration of the link between the natural world and the world of aesthetic appreciation. The link Safina says is in our ecology and the place we as humans have in it:

Life is — more than anything else — a process; it creates and depends on, relationships among energy, land, water, air, time, and various living things. It’s not just about human-to-human interaction. It’s about all interaction. We’re bound with the rest of life in a network, a network including not just living things, but the energy and non-living matter that flows through the living, making and keeping us all alive as we make it alive.

Steve MIller, “WiFi Favella” (2015) pigment dispersion and silk-screen on canvas, 79 x 69 inches

Miller also explains in his own brief introductory essay that many of the images here are generated by a long-term project that began with his travel to Brazil and into the Atlantic rainforest. He talks about the biodiversity he witnessed and the varied vantage points: on the ground surrounded by the forest, flying overhead in a plane at 2,000 feet, and looking at the land clearing operations via satellite imagery. Miller sensed the precarity of that environment and the interconnectedness of all the creatures inhabiting it. Miller figured out that one’s perspective produces qualitative differences in what one actually sees. With this conceit and some technological wizardry Miller has made a collection of images that is at times wrenchingly beautiful and a bit elegiac.

Miller uses various technologies to see inside objects and creatures: X-rays, CT scans (which use X-rays to build up a three-dimensional portrait), MRIs, sonograms, and electron microscopy. It’s fascinating that, in a way, the work does what the horror genre does (albeit without creating a lot of dramatic tension before the reveal): turn what is supposed to be on the inside out, so that the viewer is subjected to a kind of visual transgression. Horror works as a genre, I think, because, aside from fear and revulsion, surprise and curiosity occur as well.

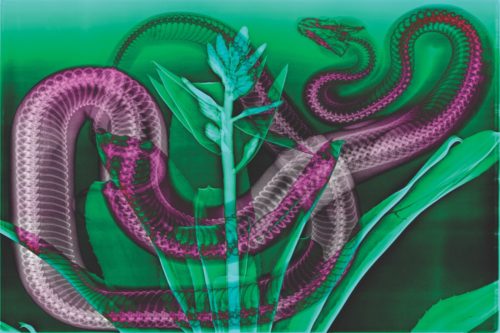

HOP 646, September 23, 2013, Inkjet, silk-screen on paper, 29 x 24 inches

HOP 646, September 23, 2013, Inkjet, silk-screen on paper, 29 x 24 inches

I experience all of the above looking at “River Raptors” (2011) a ghostly flotilla of Piranha in formation, whitish-gray against a deep black field, their mouths slightly open, their pointed teeth like ravenous jigsaws. Miller also pans his viewing angle wide to take in flowers, plants, assorted sea creatures, birds, guitars, purses, and on. This tome is not the size of a coffee table book, but it would work as such. There are enough images of creatures made gracefully alien here that casually leaving the book open to the image “Torch Snake” (2011) — an overleaf of a magenta and green X-ray image of a sinuous snake and tall plant with fanning leaves — would be sure to generate conversation.

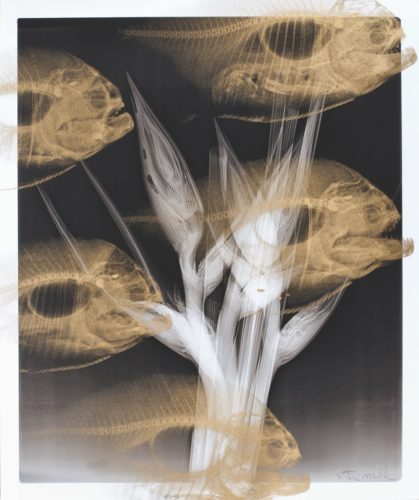

Steve Miller, “Glass Times Square” (2008), inkjet, laminated glass, steel, 31.5 x 32 x 1 inches

At times the work is too decorative for my taste, such as in the piece “Health of the Planet #525 (2009) with its flower stalk superimposed over an image of three clay jars, against a black background that is smeared with white as if this were an accidental print that stumbled into beauty. It looks like the cover image for an upmarket collection of thank-you cards. At other places in the book, the images are too busy, too layered and washy as in “Fragmentary Traces” a combination of wires and weeds, stalks and thin pigments all roiled into a frame that means to show its energy cannot be contained. Or Miller goes too far is the impressionistic bent he has in “Turtle Lungs” (2012) where without the title, I have no idea what I’m looking at.

But then Miller creates some loveliness. As in “Law of the Jungle” which has a black-and-white X-ray of a snake with a mouse deep in its digestive tract. The piece “Glass” (2008) and “Tulips” (1996) are simple compositions: just flowers made transparent and even more ephemeral in their bodies. One gets a sense of how fragile the objects can be in real life. In “Tulips” they bending slightly with the weight of their heavy heads and that is enough to evoke for me the vulnerability of this planet.

Steve Miller,”Sloth Pieta” (2011) carbon inkjet on cotton rag, 26 x 24 inches

Ultimately, in the collection of images, one can see the painter and contemporary image maker that is Miller vying against the Miller who is a more sentimental chronicler. I believe the latter makes stronger pictures. In the image “Sloth Pieta” (2011) he has taken an adult sloth and its child and rendered them wraiths against a starkly black background. Still one sees the protective arm of the adult surrounding the child with their bones intermingling as their heads touch. It’s a refresh of the classic Christian motif, and a blending of art and science that lets us see through these creatures, but not see beyond them.

Radiographic: X-ray Photo Inventions (2017) by Steve Miller is published by Glitterati press (New York and London).

Read the original article at Hyperallergic