IN STUDIO – Steve Miller and X-Ray Art

September 3, 2014

Artist Steve Miller works in a light-filled space near the train tracks along a rural stretch of land in Sapaponack on Long Island’s East End. Miller’s studio was initially built as a train station for the Long Island Rail Road—one of the few, he notes, that had a wall segregating white passengers from the African-American migrant laborers who lived in nearby camps and frequently used the stop. Then in the 1940s, the building was converted from a train station into a potato barn“A concrete road was built for potato trucks to go to the end of the building,” Miller explained in a recent interview. “The potatoes were conveyered up and went down chutes and the best were bagged and graded. “Then the potato industry hit the skids,” Miller said. “The water content of potatoes grown here was too high for the frying that McDonald’s and other fast food restaurants needed—the potatoes would explode in the fryer. The big potato buyers were fast food restaurants and this place didn’t provide the right kind of potato.” That’s when the artists moved in and the building came into the hands of abstract expressionist Neil Williams and minimalist Frank Stella who renovated the space and made it their studio in the 1970s.“In 1980 I started renting it,” Miller recalled. “Frank was done with the Hamptons. It was too trendy for him.” Miller eventually was able to buy the building in 1986. These days the train, the wall, the potatoes and Williams and Stella are gone; what continues is the making of art.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Fish Circle.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Fish Circle.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

A good portion of Miller’s artwork is inspired by the Amazon rainforest—specifically its flora and fauna. With the help of radiologists in Brazil, Miller used x-ray technology to photograph the plants and animals of the region. Starting with that imagery, he has gone on to create a series of works that explore the state of the rainforest and the globe. His unique and powerful photos depict a variety of species of fruit, flowers, fish, mammals and reptiles, and these images have been re-interpreted through a range of different mediums, from prints and surfboards to paintings.

Steve Miller in the studio. Photo by Annette Hinkle.

Steve Miller in the studio. Photo by Annette Hinkle.

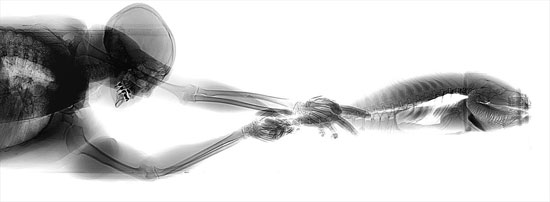

“Piranha School Black On White 009? by Steve Miller, 2014. 87.5 x 22 inches.

“Piranha School Black On White 009? by Steve Miller, 2014. 87.5 x 22 inches.

.

Now, Miller is delving into the realm of outdoor glass sculptures. Five sculptures with imagery from Miller’s “Health of the Planet” rainforest series are on view through October 11, 2014 at LongHouse Reserve in East Hampton. The works are large and were created by the transfer of his x-ray imagery onto laminated glass panels embedded in stainless steel bases painted to reference the colors in the image. Because they are printed on glass, the animals and plants depicted appear to literally float in space, and Miller feels gardens like the one at LongHouse provide an ideal backdrop for work with this kind of transparency.

.

“Iguana” by Steve Miller.

“Iguana” by Steve Miller.

.

“Iguana” by Steve Miller.

“Iguana” by Steve Miller.

.

“It’s so cool to see these sculptures outdoors with the animal floating in space,” he said of the LongHouse exhibition. “The grasses growing up around them make it look like the snake is in the grass. They have an organic relationship to the landscape.”

.

“Serpent” by Steve Miller.

“Serpent” by Steve Miller.

.

“Serpent” by Steve Miller.

“Serpent” by Steve Miller.

.

“Nature in the garden. My stuff works well in that environment,” he said. “In a weird way, it’s like a tombstone. It sort of tells you something about the future.” The sculptures are new for Miller and he admits there has been a bit of a learning curve in devising the process to make them. In his studio sits an example of the sculpture with one of Miller’s most iconic images: an x-ray of a mother sloth embracing a baby sloth.

.

“Sloth Pieta” by Steve Miller.

“Sloth Pieta” by Steve Miller.

“It’s the ‘Sloth Pieta,’” Miller explained, adding that this particular piece was not suitable for outdoor display because of printing and lamination flaws in the production process, which is why the artist has kept it in his studio.“These guys are dying for our sins,” Miller said of the sloths. “That’s sort of to me the metaphor.”

.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Sloth Pieta.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Sloth Pieta.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

.

Because it can’t be used outdoors, to add a punctuation mark to his statement on the state of the planet, Miller had a friend fire a gun at the glass over the sloth’s heart, which is pock-marked and cracked by the impact of the bullet. It’s a not so subtle illustration of the looming threat animals like these face in the wild.

.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Sloth Pieta.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

Steve Miller in the studio with “Sloth Pieta.” Photo by Annette Hinkle.

.

The origins of Miller’s interest in his rainforest subjects can be traced back to 2005 when he traveled to Brazil to participate in an art show. He was amazed by the beauty of Ilha Grande, an island near Rio De Janeiro, and was particularly intrigued by the huge jaca fruit trees that grew there. “I thought, ‘What’s in these?’ Miller said. “I thought it would be cool to x-ray one.” Two years later, Miller found a radiologist in a Sao Paolo hospital who would allow him to bring objects in for x-raying.The process seemed to be a perfect metaphor for his art.

.

Artwork by Steve Miller.

Artwork by Steve Miller.

.

“My idea was if the Amazon is the lungs of the planet, I’ll x-ray the lungs and give Brazil and the planet a medical check up,” the artist said. “So we go into this flower market warehouse which is full of watermelon and jackfruit. I found this jackfruit with two on one stem, and that never happens.” “They looked like lungs when I x-rayed them,” he said. Then Miller discovered Belém, the largest city on the Amazon,which had a fishery, an aviary and a zoo all housing rainforest plants and animals. “The aviary and zoo had no access to x-rays, and they wanted to x-ray the animals for different reasons,” Miller said. He worked with radiologists to x-ray as many animals as he could while he was there, including a school of piranhas and a live alligator.

“I’ve got two or three technicians there, they’re working for me for free, staying late,” the artist recalled. “I’m making a mess of the place, I do feel the pressure. But I don’t know what I’m doing.” While he was able to capture many amazing images during the process, the most poignant was also the most tragic. The female sloth was brought into be x-rayed when she was near death. The people at the zoo wanted to see what was going on in the animal’s lungs.“The sloth habitat is being destroyed. They’re getting isolated,” said Miller. “Their defense system is hanging higher in trees and clamping on. Once you remove those trees they have no where to go and can’t migrate. Their food source and defense is gone. When they clear trees they burn them and sloths are also sensitive to air pollution.”

“These things are incredibly complex,” Miller said of the Amazon’s interdependent plant and animal life. To contrast the elegance and complexity of their makeup with human society and its furnishings, for a 2011 exhibit in Brazil the artist displayed images of the animals alongside x-rays of fashionable manmade objects—like Chanel bags. “Isn’t this interesting? Piranhas are complex machines you could never design and they eat dead animals and clean the river,” he said. “They have this function to enhance the ecosystem.” “Then how complex is the design of the purse? Yet we value this more,” he added. “I called the show ‘Fashion Animal’ to create that awareness.” With the idea of raising awareness in mind, the artist has made his rain forest imagery available on a line of high end t-shirts and swim trunks produced by Osklen, a sustainable eco-sensitive clothing manufacturer in Brazil. “You can use the fashion as a billboard for these ideas,” said Miller. “They may not go see a gallery show, but now people can come to my work through more accessible platforms.”